U.S. Embassy in Kabul

I’m a former member of Congress, cybersecurity executive, and officer in the Central Intelligence Agency. “American Reboot: An Idealist’s Guide to Getting Big Things Done” is my first book. Learn more about why I wrote American Reboot.

“American Reboot” is a classic American story and a blueprint to build a future based on the shared values that have solved the challenges of the past.

Read an excerpt below:

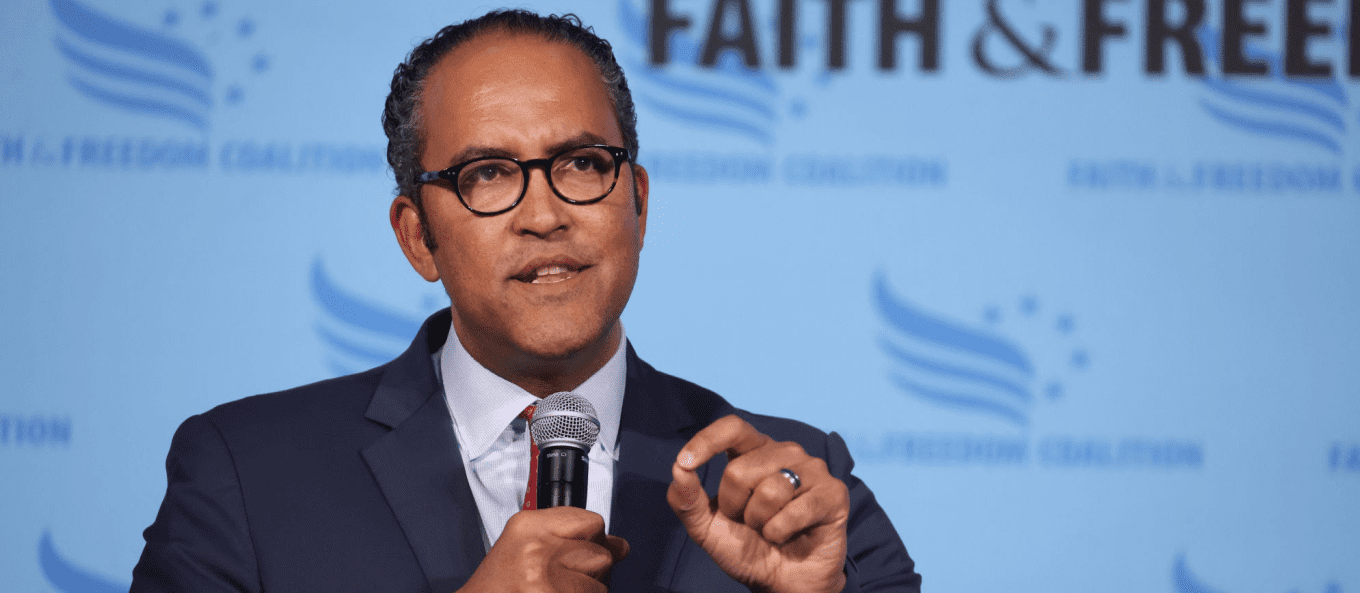

In October 2000, shortly after graduating from A&M, I joined the CIA. After taking two journalism classes in Mexico City the summer after my freshman year, I added international studies as a minor. In the first class I took for my new minor, I had a guest lecturer who was a badass former CIA officer named Jim Olson. He told the most amazing stories about the National Clandestine Service, and I knew I wanted to do what Jim had done. I submitted an application, took a bunch of tests, and was grilled during tons of interviews before I was hired. For almost a decade, I recruited spies and stole secrets all over the world. My responsibility was to stop terrorists from conducting attacks around the world, prevent Russian spies from stealing our secrets, and put nuclear weapons proliferators out of business. I was working at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, when the world acted in unison following the attacks on the U.S. Homeland by al-Qa’ida on September 11, 2001; and I was operating on the ground in Kabul in 2009 when debates raged about whether the war in Afghanistan required a “surge of troops.”

For almost a decade, I recruited spies and stole secrets all over the world.

In addition to collecting intelligence, I was called upon to brief members of Congress. In late 2008, a congressional briefing in Afghanistan changed the trajectory of my life, and that day began with a resonating boom at four a.m.

I shot upright in bed, trying to figure out if it was a dream or real life. The window rattled so hard that it nearly shattered. I wrapped myself in a blanket, rolled off the bed and onto the floor.

“Duck and cover, stay away from the windows, seek shelter, and await further instructions,” a pre-recorded voice blared over the speakers through- out the apartment complex where most of the American employees in Kabul lived.

I was the head of a branch in the CIA station, and I knew the chief of station—the senior-most CIA officer in Afghanistan and my boss—would task my unit to figure out who had carried out this attack.

I verified the safety of the officers under my command and instructed them to assemble in the secure conference room once the all-clear signal was given. I slid my nine-millimeter Glock 19 pistol into a concealed leather holster in the back of my pants, pulled a black sweater over my Kevlar body armor, and left my apartment to get to work.

When the all-clear was sounded, my trusted deputy, Heather, and I met with our team, providing them with a comprehensive summary of what we had learned about the attack. Before outlining a plan of action, we asked each officer whether they had people within their stable of recruited assets and contacts who might be able to provide insights on the morning’s events.

I needed information by that afternoon, because I would be asked about it during a scheduled briefing for a congressional delegation from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) that happened to be visiting. HPSCI (pronounced “hip-see”) is one of two congressional committees devoted to monitoring intelligence activities on behalf of the American people.

As I walked into the conference room for the briefing, I overheard several Congressmen ask the person handling the logistics for their visit: “Is the CIA going to cut this briefing short so we can get to the bazaar to buy rugs?”

Rug shopping? That’s what they were thinking about right now? I was pissed, and the briefing hadn’t even begun.

During the ensuing conversation, I was asked why we weren’t seeing more cooperation between the Taliban and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). I began explaining how the Taliban was Sunni and the IRGC was Shia.

One of the Congressmen raised his hand and asked, “What’s the difference between a Sunni and a Shia?”

I assumed he was going to make a terribly inappropriate joke. And who was I to stand in his way? So I played along.

“I don’t know, Congressman—what’s the difference?” I asked with a big smile.

The congressman’s chubby face turned bright red, his eyes widened, and his body stiffened. He had no idea what the difference was between the two main sects of Islam. Not a freaking clue.

The congressman’s chubby face turned bright red, his eyes widened, and his body stiffened.

It’s okay for my brother Chuck not to know this, because as a cable company sales manager, this piece of information isn’t important for him to know. But this should have been easy stuff for these Washington, DC, intelligence “experts.” They were determining how to allocate billions of taxpayers’ dollars on national security. They were making decisions on sending our sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, to war zones. But they lacked a basic understanding of one of the greatest global threats facing the U.S. and the rest of the world, and they were more interested in going rug shopping.

My mom would always tell my siblings and me, “You’re either part of the problem or you’re part of the solution.” It was time to be part of the solution.

A year or so before the Kabul briefing, the solution had been introduced to me at a Tex-Mex restaurant in Washington, DC, by Stoney Burke, one of my closest friends, and his best friend from college, a wily political operative named Josh Robinson. Stoney gave me the idea to run for Congress in Texas 23, and Josh gave me the plan. Ever since that first conversation at La Lomita Dos, Josh, an early mentor to Justin Hollis—the guy who would oversee all my successful elections as my campaign manager and political consigliere—gave me the confidence that I could do it.

I was an unlikely congressional candidate. Before I ran, there wasn’t a big history of people from the CIA running for office. A rare exception was Porter Goss, a former CIA office who served in the House for fifteen years before going on to serve as CIA director and in other key leadership posts. Elective office is more of a career destination for former military officers or lawyers. It wasn’t considered a traditional path for an A&M computer science major who had been in the CIA and hadn’t lived in Texas for a decade.

Stoney and Josh Robinson pointed out that serving in Congress would be a way to address problems that had frustrated me in the CIA—including ignorant congressional Representatives who preferred rug shopping over doing their jobs. They opened my eyes to the notion that it was a chance to use my CIA skill set to provide a different perspective on national security issues.

Because Texas 23 includes portions of San Antonio, it was a natural place for me to run because it was where I was born and raised, although most people I knew thought I was crazy to leave a job I loved and was good at. But I had to follow my mom’s advice to be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

American Reboot debuts on March 29, 2022. It’s available NOW for pre-order here.

Excerpted from “American Reboot” by Will Hurd. Copyright © 2022 by Will Hurd. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.